Energy efficiency, once dismissed as “Jimmy Carter trying to persuade [Americans] to wear an extra sweater and turn down the thermostat,” is now a booming high-tech industry, according to a report last week in the L.A. Times.

American electricity providers have tripled their spending on energy efficiency programs since 2006, the piece reports, and spending on efficiency technologies and programs reached $250 billion worldwide last year. According to the International Energy Agency, which compiles the numbers, spending could hit $500 billion by 2035. The flurry of activity not only involves new technology and efficiency upgrades, but an enormous growth in the use of data by power providers and other firms to profile customers’ energy use to recommend savings and improvements.

Google Inc. dropped $3.2 billion this year to purchase Nest, a company which designs high-tech thermostats that predict their owners needs — for example, precooking a home before the owners return from work. That allows utilities like Southern California Edison to smooth out load on the grid, moderating they big spikes in electricity demand that usually occur in the evenings. Meanwhile, data-mining companies like FirstFuel can pull thousands of data points from a home-or-business owners’ smart meter, check that against other information like weather history, and provide the customer with an extensive energy-use profile that comes with all sorts of suggestions for improving efficiency — all without an auditor ever setting foot on the property.

Then there’s Retroficiency’s Building Genome Project, which went through publicly available data on 30,000 buildings in New York City to show how enormous amounts of energy good saved with slight modifications.

“Millions and millions of dollars have been spent trying to figure out which buildings are inefficient,” said Retroficiency’s chief executive, Bennett Fisher. “Doing it manually has created a bottleneck. We want to blow open that bottleneck.”

Energy efficiency is one area where, by all accounts, there is a massive amount of low-hanging fruit to be had in terms of both energy use reduction and cutting greenhouse gas emissions. A study at the end of 2013, for example, showed how the average building in the nation’s own capital of Washington, DC wastes a great deal of energy — and how the savings from an efficiency upgrade would far outweigh the costs of the retrofit.

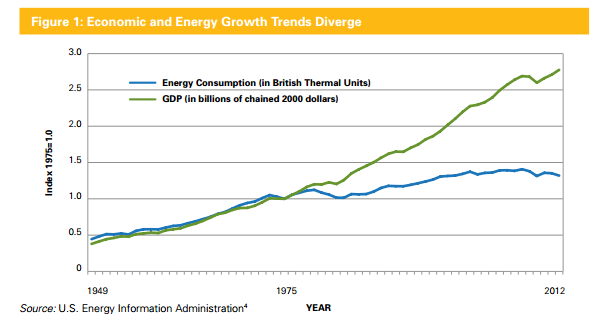

And the push is already underway: the last two updates to the International Energy Conservation Code — a building efficiency standard widely employed by state and municipal governments — resulted in combined efficiency gains of 30 percent. Nationally, energy consumption has increasingly diverged from economic production since the 1970s, with the former slowing while the latter continues apace — suggesting the American economy is getting better and better at doing more with less energy.

The International Energy Agency has shown that a collection of countries — including the U.S., Britain, France, Germany, Australia, Japan, Italy, and several Nordic nations — avoiding burning the equivalent of 1,500 million metric tons of oil in 2010 thanks to efficiency improvements. And that number has been steadily increasing since the 1970s as well.

In America, those improvements have been helped along by a number of state-level energy efficiency targets that have helped lay the groundwork and the market incentives for the current boom in energy efficiency firms. And while energy efficiency programs at the national level have been harder to come by, the Obama Administration’s new rules for reducing carbon emissions from the nation’s power plants include efficiency programs as one of the options, aiming for an overall increase of business and residential energy efficiency of 1.5 percent per year.

Admittedly, all this mining of energy-use data has raised concerns among privacy advocates. The LA Times noted at least one instance last year where immigration authorities, drug enforcement agents, and state tax officials issued more than 1,110 subpoenas for records of energy use from customers in the San Diego area as frequently as every 15 minutes. A big part of the problem is that the energy efficiency market sector is still fairly new. So laws, best practices, and utility methodologies are still being developed, all of which will be the focus of a fall conference sponsored by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

“This is a big deal,” said Neal Elliott, the associate director of the conference. “But it is not a big deal unique to energy.”